by Michael Woodhead

[This is an account of a trip I made to Blagoveshchensk in September 2015. It's a Russian town on the Amur river, bordering North East China (Manchuria). China and Russia share a long border, more than 4000 km long, but there is only one place where Chinese and Russian cities actually face each other in close proximity: Blago and Heihe. It's a fascinating area where Asia meets Europe. I travelled there via Harbin in China, as it is a lot cheaper, and I speak Chinese - but not Russian.]

[This is an account of a trip I made to Blagoveshchensk in September 2015. It's a Russian town on the Amur river, bordering North East China (Manchuria). China and Russia share a long border, more than 4000 km long, but there is only one place where Chinese and Russian cities actually face each other in close proximity: Blago and Heihe. It's a fascinating area where Asia meets Europe. I travelled there via Harbin in China, as it is a lot cheaper, and I speak Chinese - but not Russian.]

When you arrive in the northern Chinese city of Heihe on the Amur river you might be forgiven for thinking that you have already arrived in Russia. The street signs are in Cyrillic and all the shops have bilingual signs. If you are European you'll be approached on the street by Russian-speaking Chinese shop touts who implore you to enter their outlets selling cheap clothes and electronics. The parks of Heihe are landscaped with bushes sculpted in the shape of Russian church domes and there is even a "Pushkin Bookshop" on the city’s pedestrian shopping mall. The only thing missing in this Sino-Russian border trading outpost town is Russians.

Until last year, Russians used to come across the river in their hundreds every day into Heihe to snap up cheap goods. They came from Blagoveshchensk, Heihe's 'twin town' located just a 100 metres distant on the opposite bank of the Amur river. But since the collapse of the value of the rouble against the Chinese yuan in 2014, the Russians have been staying away in droves. They simply can’t afford Chinese goods any more.

On my first morning in Heihe the only Russian I saw was a bronze statue of what are known locally as “bricks” – the traders laden down with huge sacks of merchandise. Until last year the 'bricks' were the lifeblood of Heihe. Usually students or retired folk, the 'bricks' took advantage of the twin-city agreement between China and Russia that allows locals visa-free travel between the respective cities of Blago and Heihe. Crossing the river on the 10-minute ferry trip they would load up large rectangular bags full of cheap clothes to take back for sale in Russia. Now, however, thanks to the crash in oil prices and the western economic boycott of Putin's Russia, the rouble has depreciated enormously against the yuan, leaving the ‘bricks’ with no profits - and no reason to come to China.

“Three years ago the exchange rate was three

or four roubles to the yuan and bricks could make 3000 or 4000 yuan profit a

day,” says Ilya, a Russian ‘biznis’ man whom I later met in Heihe

“Three years ago the exchange rate was three

or four roubles to the yuan and bricks could make 3000 or 4000 yuan profit a

day,” says Ilya, a Russian ‘biznis’ man whom I later met in Heihe

“These days the exchange rate is 10 roubles

to one yuan, and the bricks might only make 500 yuan a day - and that’s not enough to even pay for

the ferry ticket,” he told me.

“This

street used to be full of Russians,” says Lena, the Chinese proprietor of a

Russian-themed restaurant that bears her name on the main street of Heihe. Her restaurant serves borscht, kebabs and salad and Baltika beer, but at 7pm I'm the only

customer and she is preparing to close up shop.

“Everything has gone quiet due to the poor

economic environment in Russia, but things will pick up again eventually, I’m

sure”, says Lena, who learned Russian when she was living and studying ‘across the

river’ for several years.

Other Heihe traders are not so optimistic. “Business used to be good here but I can’t see any future now,” says a man called Chen standing outside a deserted clothing store on Heihe’s Wenhua Street.

“The Russians don’t come any more and even the

ones who do only want to buy the cheapest things for 100 roubles - I can’t even

break even at those prices,” he says. “I’m thinking of moving to Fujian, where business is

better,” he tells me.

By Chinese standards, Heihe is a clean, green and pleasantly uncrowded city. It has many new high rise apartments along the banks of the Amur river, and the city planners have created a swathe of landscaped parks, squares and gardens. But it's almost a ghost-town. The city’s wide three-lane highways are devoid of traffic, except for a few folk pedalling the bright green bikes that the city provides as part of its self-hire public bike scheme.

The roads in Heihe all seem to lead to the huge concrete arch of a bridge that connects the downtown area to the "Big Island" in the river, which contains the stadium-like brushed steel "China-Russia Free Trade Centre". However, when I visit the centre, I quickly discover that this landmark development is padlocked and deserted, the Chinese and Russian flagpoles bare. Only the few faded Cyrillic character advertisements for mobile phones give any clue of its former business activity. Business-wise, Heihe is a town in suspended animation.

The trade centre overlooks the Amur river, along which there is a narrow strip of pebbly ‘beach’ on which a handful of Chinese locals are braving the cooler temperatures of autumnal September to swim in the fast moving current. A few other locals are washing laundry in in the river and some are fishing, but most visitors just come to look at the other side - Europe.

On the walkway above the river a stone plinth bears the red seal of China and marks this as the national border. Chinese tourists pose for photographs beside it, and peer across to the Russian side of the river, which is just a few hundred metres away. The distance is about the same as looking across the Thames at Westminster. It's close enough to see Russians going about their daily business - strolling the waterfront or riding bikes, living in a parallel universe but seemingly oblivious to their Chinese neighbours.

On the Russian bank of the river there are a few high rise buildings but also some grand European-style Russian buildings can be seen dotted along tree-lined waterfront. At a viewing area on the Chinese side I pay 3 yuan to use some high power binoculars to observe the other side. I see a few Russians are lounging on the beach. None of them are swimming. There is also a large concrete watchtower and a heavily armed Russian patrol boat is moored silent and sinister in the mid-river. On the Russian shoreline I see a line of green-uniformed soldiers with guard dogs jogging along the beach. It looks like a rehearsed drill as they peel off and take up pre-arranged positions, crouching with their dogs and cradling their rifles, among the indifferent sunbathers.

On the Chinese side there is no such

security. A hawker paces up and down selling melon seeds and ice creams. Instead of a patrol

boat there is a tourist cruise boat moored at a makeshift jetty, with a crackly loudspeaker that plays a loop of an

excited lady’s voice inviting would-be customers for a 70 yuan one-hour river sightseeing cruise.

Two young Chinese guys stare across the river and one says “Russia”. His friend gestures towards Blagoveshchensk with his chin in the Chinese manner and uses the name "Hailanbao", the traditional Chinese name for the Russian city.

Two young Chinese guys stare across the river and one says “Russia”. His friend gestures towards Blagoveshchensk with his chin in the Chinese manner and uses the name "Hailanbao", the traditional Chinese name for the Russian city.

The

waterfront street in the centre of Heihe is lined with tacky faux-Russian architecture. One of the buildings contains the Heihe Museum, but it is closed to Russians and other Europeans like myself. I later find this is because of the sensitive and inconvenient historical facts about Russian-Chinese conflicts over the Amur region, which are quite at odds with the current friendly relations between the two superpowers.

Online articles by Chinese bloggers show that the Heihe museum depicts the Russian territory around Blago as being Chinese territory, stolen by Russia. According to the Chinese history books, the area around Blago was first settled by Chinese gold miners, traders and farmers during the Manchu Qing dynasty. The Russians, however, say that the north bank of the Amur river was also home to Russians as early as the 17th century. It was annexed during the Tsarist-era expansion of Russia into Siberia and the Far east in the 19th century and the seizure was enforced by the 'unjust' Aigun Treaty of 1858. Chinese settlers continued to live in the area around Blago, under de facto Qing administration even after this treaty was signed, and the area was know as the "64 Villages".

During the Boxer rebellion of 1900 the dispute over the Amur river territory turned violent. The Russians say that Blago was a defenceless town, besieged by Qing-backed forces who had attacked and destroyed Russian railway lines and massacred any Russian citizens the encountered in outlying areas. The local people of Blago organised their own defence against the Chinese who were shelling the town and firing at boats on the Amur river. Supported by Cossack troops, the defenders of Blagoveshchensk then expelled the local Chinese who were sympathetic to the Qing.

The Chinese version of events has it somewhat differently - that the Russians expelled all 5000 Chinese civilians - including women and children - from the north bank of the Amur by literally driving them into the river. There were no boats to cross the river and those Chinese who did not drown in the waters were shot or bayoneted by Cossack forces. The Chinese museum exhibits depict the Russians as murderous brutes, and they are still known colloquially as "Lao Maozi" - Hairy Barbarians.

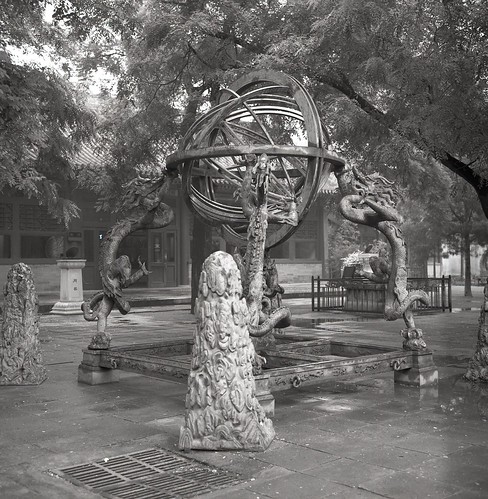

In public, however, the Chinese authorities of Heihe nowadays emphasise the good relations between China and Russia, and their mutual alliances in more recent history. In Heihe's riverside park, the Chinese have erected a large war memorial on which are engraved the names of about 100 Soviet Red Army soldiers who died fighting the Japanese Kwantung occupation army during the Russian invasion of Manchuria in August 1945. An old Chinese man who sees me reading the Russian names assumes I am Russian and gives me a thumbs up signs and says “Harosho!” (Russian for ‘Good’!).

Online articles by Chinese bloggers show that the Heihe museum depicts the Russian territory around Blago as being Chinese territory, stolen by Russia. According to the Chinese history books, the area around Blago was first settled by Chinese gold miners, traders and farmers during the Manchu Qing dynasty. The Russians, however, say that the north bank of the Amur river was also home to Russians as early as the 17th century. It was annexed during the Tsarist-era expansion of Russia into Siberia and the Far east in the 19th century and the seizure was enforced by the 'unjust' Aigun Treaty of 1858. Chinese settlers continued to live in the area around Blago, under de facto Qing administration even after this treaty was signed, and the area was know as the "64 Villages".

During the Boxer rebellion of 1900 the dispute over the Amur river territory turned violent. The Russians say that Blago was a defenceless town, besieged by Qing-backed forces who had attacked and destroyed Russian railway lines and massacred any Russian citizens the encountered in outlying areas. The local people of Blago organised their own defence against the Chinese who were shelling the town and firing at boats on the Amur river. Supported by Cossack troops, the defenders of Blagoveshchensk then expelled the local Chinese who were sympathetic to the Qing.

The Chinese version of events has it somewhat differently - that the Russians expelled all 5000 Chinese civilians - including women and children - from the north bank of the Amur by literally driving them into the river. There were no boats to cross the river and those Chinese who did not drown in the waters were shot or bayoneted by Cossack forces. The Chinese museum exhibits depict the Russians as murderous brutes, and they are still known colloquially as "Lao Maozi" - Hairy Barbarians.

In public, however, the Chinese authorities of Heihe nowadays emphasise the good relations between China and Russia, and their mutual alliances in more recent history. In Heihe's riverside park, the Chinese have erected a large war memorial on which are engraved the names of about 100 Soviet Red Army soldiers who died fighting the Japanese Kwantung occupation army during the Russian invasion of Manchuria in August 1945. An old Chinese man who sees me reading the Russian names assumes I am Russian and gives me a thumbs up signs and says “Harosho!” (Russian for ‘Good’!).

“China-Russia relations are very close!

America and Japan are our real enemies!” he says in Chinese.

Further on in the pedestrian precinct of

Heihe I am accosted by more local Chinese speaking to me in pidgin Russian, but they

are are more interested in closer commercial relations than strategic ones.

When I speak to them in Mandarin they

recoil with surprise, but then relax and let their guard down when they learn I am not Russian.

“You speak Chinese - the Russians don't,” says

one female selling mobile phone accessories in the huge electronics and

clothing emporium.

Despite living just across the river and

hundreds of kilometres from the nearest Russian city of Khabarovsk, few residents

of Blagovaschesk speak any Chinese, she tells me.

And like many locals she asks: “If you’re

not Russian, what are you doing here?”

“On my way to Russia,” I tell her.

When I eventually spot some Russian visitors on the streets of Heihe, they are guarded and uncommunicative. Although I must be the only other non-Chinese face in town, they ignore me and don't acknowledge my presence. They don't look like affluent tourists: the men wear tracksuits or cheap jeans and look rather down at heel, while the women appear slightly overdressed and seem intent on driving a hard bargain with the Chinese touts at the ubiquitous “P100” (100 roubles = $1.50) shops.

I seek refuge in the Pushkin Bookshop,

which I quickly discover is actually just a rebadged Xinhua Bookstore of the type found in every

Chinese town and city. The interior has been given a makeover with fake and over-the-top

pseudo-Russian décor. When I ask the bored store manageress if they have

any Pushkin books in Russian she leads me to a dusty bookshelf in a gloomy corner at the back of the store where there are a

handful of cheap Chinese-published reproductions, seemingly untouched.

I seek refuge in the Pushkin Bookshop,

which I quickly discover is actually just a rebadged Xinhua Bookstore of the type found in every

Chinese town and city. The interior has been given a makeover with fake and over-the-top

pseudo-Russian décor. When I ask the bored store manageress if they have

any Pushkin books in Russian she leads me to a dusty bookshelf in a gloomy corner at the back of the store where there are a

handful of cheap Chinese-published reproductions, seemingly untouched.

“Do you sell many?” I ask.

“No, the Russians don’t come here to buy

books,” she replies.

The Pushkin Bookshop appeared to be doing more business from wedding and portrait photos than from selling books, judging by the prominence of the photographic gear and lights set up next to shelves full of fake leather-bound classics. The bookshop was also the place in Heihe to be seen drinking cappuccino in an ornate setting. But Russian visitors to Heihe tended to prefer something stronger to drink.

Across the road, I found a couple of Russian guys drinking beer and eating shaslik kebabs in the outdoor ‘beer garden’ of the Café Moskow. Ilya, who spoke a little English but no Chinese, told me that the courtyard area had been the traditional cheap accommodation centre for Russian traders staying overnight Heihe, where rooms could be had for as little as 200 roubles (20 yuan). He said Russians could come visa-free to Heihe for 30 days, but the Chinese were only allowed to visit Russia visa free if they came as part of a group tour.

“There used to be many Chinese traders in

Blago but now they’ve all gone home,” he told me. “Some of them had been living in Blago

for years but when the trading conditions turned bad last year the Blago government closed

down their hostels and kicked them out,” he said.

The next day I travelled across the Amur

river to see for myself. Armed with a Russian visa, I took a taxi over to the ‘Big Island’ where the customs and immigration hall for crossing

between China and Russia was located. Cross-river ferries ran every hour, but

they were segregated with separate boats for Chinese and Russian

passengers.

The Chinese treated the Russians brusquely, as I found when I tried to buy a ticket for the Chinese ferry. I was shouted at and shooed away towards a handful of young Russian men waiting in the line for passport control. They were all toting large bags of merchandise. I was last in line and the bored Chinese immigration official did a double take when he saw my Australian passport, and immediately sat up and called his superior.

“Why

are you here and what is your reason for going to Russia?” I was asked, curtly.

They warmed slightly when they discovered

I could speak Chinese.

“Just for sightseeing” I told them.

They sniggered when they saw my

folding bike and I told them that I was planning on cycling in Russia.

“Good luck with that!” they said, as they

stamped my passport and pointed me down the gangway towards a waiting ferry.

After the rigmarole of immigration control and boarding the ferry, the actual river crossing was so quick it was a complete anticlimax. The journey from the Chinese to the Russian bank of the river took only five minutes, hardly enough time for the Russian crew members to notice that I was not Russki and to further fuel my doubts about cycling in Russia. “Velo-tourism?” asked one deckhand, pointing to my bike and miming pedaling with an incredulous expression, shaking his head. "Nyet!"

Before I knew it we had docked at the Russian wharf and ushered off past some mothballed

hovercraft towards a large arrivals hall. Standing in line I felt slightly apprehensive from

being unable to barely speak a word of Russian, and my confusion was enhanced

by the realisation that I was now suddenly in Europe rather than Asia.

Everything seemed bigger, neater and more orderly – and quieter to the point of

lethargy after the chaos of the China that I had left behind just a few minutes

earlier.

The Russian immigration woman might have

been specially selected to represent every European stereotype, so as to

contrast with the Chinese. Tall, with blonde pigtails and a starchy uniform and

ultra-white blouse and black tie, she gave me a severe look when I uttered my much-rehearsed

phrase in response to her quick-fire Russian question. “Ya ne gavaryu pa Russki,” I said apologetically.

She ignored my profession of ignorance about the language and fired off more questions at me in

Russian. I shrugged my shoulders and she eventually gave up with an impatient sigh and called over a supervisor who spoke a

few words of English.

I then made the mistake of volunteering

that I could speak Chinese, and asking if this might help communication. The

two of them looked at me with a mixture of amusement and ridicule, and

completely ignored my suggestion.

I was made to fill in extra forms, and after

conferring for about five minutes and flicking through my passport, their

attitude seemed to soften into curiosity.

“Michael … Sydney?” said the woman. “Afstralee?”

She stamped my passport and handed it back to me.

“Welcome …” she said, her first word in

English, and pointed me towards the door with a bemused “You’ll be sorry” look.

Part 2: Blagoveshchensk

In Blago, I was suddenly back in Europe. Even though the Chinese buildings of Heihe were prominent in the background as I walked along the waterfront, I found myself passing outdoor cafes selling kebabs, pizza and

burgers. Mums pushed babies in prams and groups of teenagers huddled awkwardly,

sniggering as I went past. A few moments earlier in China I had been a

‘foreigner’ who stood out in the street. Now I was anonymous again, just

another face in the European crowd.

Near an ornate Tsarist-era arch on the waterfront I sat down for a beer at the pleasant outdoor cafe-bar of

the Hotel Armenia, which overlooked the Amur river. The hotel was a grand mansion of red and yellow brick,

located next door to an ornate complex of buildings and palaces festooned

with turrets and domes that wouldn’t have looked out of place in St Petersburg .

But once I moved away from the waterfront and started to explore the city of Blago, I might have been anywhere in Eastern Europe. Blago was in denial about its location: there was no acknowledgement that this was a town on the periphery of China. In contrast to Heihe, there were no bilingual street signs and no shops catering to Chinese traders. While everything in Heihe seemed to be geared to trade links with Russia, everything in Blago seemed to be asserting that this was just another corner of Mother Russia. There appeared to be no Chinese people whatsoever in Blago, whose population was entirely Slavic-Caucasian. The only signs of China I could find in Blago were a few Chinese restaurants, whose signage was completely in Cyrillic - Китай (Kitay - China).

Blago also appeared to be a much older and more settled place than the scrappy boom-and-bust modernity of Heihe. The streets of Blago were laid out in a grid pattern with wide avenues shaded by rows of leafy trees. Trolley buses hummed their way past a few grand municipal buildings such as the Amur Regional Council and the Philharmonic Concert Hall. Many Tsarist-era traditional wooden houses remained, often painted in cheerful blues and yellows and they had beautifully decorative trim around the window frames and eaves. Sadly, many were in a somewhat dilapidated condition, and I could understand why most locals would prefer to live in the centrally-heated apartments of the more modern concrete tenement buildings. The weather was mild and warm in September, but this was Siberia where the temperatures dropped to minus 20 degrees in the winter months.

While Heihe had felt like a thrusting frontier town, Blago was more like a backwater. The atmosphere was sedate and slightly formal, a distinct contrast to the brash mercantilism on the streets of Heihe, where Chinese vendors stood outside their shops clapping or approached would-be customer on the street to do their sales pitch in pidgin Russian.

In the downtown shopping district of Blago there were cafes, pharmacies, supermarkets and banks just as you would find in any European city. In Russia, however, the shops did not put there wares on display in the window – everything seemed to be hidden behind heavy-duty uPVC doors and tinted windows, which along with the Cyrillic alphabet made it something of a guessing game for me as to what I would find inside.

There was no spitting and no

litter. The local pedestrians obeyed the traffic signals and waited patiently

for the green man signal to cross the street. I quickly learned this was the

sensible thing to do because the Russian drivers were fast, reckless and merciless

to jaywalkers. In Heihe the Chinese drivers' bark was worse than their bite - they sounded their horns but veered away from a collision at the

last second. In Blago, however, the drivers ploughed grimly along the roads and woe betide anyone who got in the way. On some streets I saw the same neat rows of green public-hire bikes on display, identical to the ones I’d seen across the river in Heihe. But in Blago the hire bikes were

pristine and unused. No-one, it seems, was crazy enough to risk cycling on the roads amid Russian traffic.

In Heihe there had been many brand new

Range Rovers and VW 4-wheel drives on the roads, driven by China's nouveau riche businessmen and women. In

Russia, the cars were older, more beat up and mostly Japanese – many were right

hand drive, presumably imported second hand from Japan.

I spent my first afternoon in Blago just enjoying the experience of being in a European city again – albeit in the Far East. It was strange to think that I was still in the same time zone as Australia.

In the supermarkets I noticed that the wares and their prices were similar to what I would expect to find in any other European town. The Russians obviously loved their bread – each supermarket had a wide range of freshly baked brown loaves as well as muffins, pastries and other delicacies in the on-site bakery. There was also an enormous range of sausages and salamis. I had half expected Russian shops to be like the cliches of the Iron Curtain years – bare shelves and long queues for grim fodder of potatoes and cabbage. On the contrary, provincial Russian consumers seemed to enjoy access to a wide range of foods, not to mention chocolates, coffee and ice cream.

If it were located in European Russia, Blago would no doubt be an unremarkable small city. But standing within hailing range of China, I found it a novelty to stroll along the avenues admiring the colourful stucco facades of the 19th-century civic buildings and the Byzantine gold spires of the Orthodox cathedral.

Families relaxed on the benches in the parks and wide squares with their statues of Lenin and Maxim, and I must admit I had my head turned by many of the stunningly beautiful Russian women. The women of Blago looked elegant, relaxed and confident - and they all seemed to wear strong perfume. The men, however, were a different story: the more respectable ones had the appearance of down-to-earth mechanics or technocrats. But there were a lot who looked like they'd failed auditions for The Full Monty. Blago -twin town of Barnsley? I'd expected to see a lot of vodka-soaked drunken Russians, but the blokes of Blago appeared quite sober. There were, however, some scary-looking guys in tracksuits with more tattoos than teeth. If Hollywood movie producers want extras to play villainous Russian drug gang members, they could just hire Blago taxi drivers

Growing up during the Cold War era, I'd half expected the Russians I met to live up to the stereotypes of that time: dour, suspicious and authoritarian. Instead, they were not so different from anyone you would see on the streets of Leeds or Melbourne. This was falsely reassuring because nobody spoke a word of English. Hardly surprising - there wouldn't be much call for it - or chance to practice it - when you live in the Russian Far East. But even simple transactions such as buying a coffee or trying to change money in the bank proved to be supremely difficult and prone to misunderstandings. The Russians I dealt with automatically assumed I was one of them and became impatient and surprisingly unsympathetic over my inability to speak more than a few words of their language.

I was therefore fortunate to have arranged to stay in Blago with an English-speaking family. Irina and Nikolai were young professional couple with two boisterous pre-school age boys. They lived in a cosy two bedroom apartment on the outskirts of town, where they drove me in their Landcruiser during the rush hour traffic. It was only then that I realised how much bigger Blago was than Heihe.

They prepared a wonderful traditional Russian dinner of borscht with all the extras: gherkins, limes, zucchini, egg salad and spicy tomato dip for the brown bread. Nikolai plied me with a special variety of local vodka - more like a brandy made from bird cherries, and showed me photos of his cross country skiing trips in the frozen north.

Irina and Nikolai seemed to have a good life in Blago but they told me they had considered moving away from the remote Far East to start a new life in St Petersburg, for the sake of the children. However, they had second thoughts when they visited the big city, finding it an expensive and impersonal place to start from scratch. Rents and bills were cheap in Blago compared to the bigger cities, and they had family connections there - and felt close to the land. Like many Russians, Irina and Nikolai had a small second house on a plot of land outside the city, where they grew many of the vegetables we'd had for dinner.

On the Chinese side of the river the land was intensively farmed with large strips of maize fields and other cultivated crops. Around Blago, however, the outskirts of the city gave way to birch forest, amid which were sat rustic small farms and vegetable gardens. It was all very rustic and had a 19th century look about it.

In Heihe the Chinese thought in terms of north and south. Heihe was very much North China, and like the rest of Heilongjiang, it's weather, cuisine and its customs were often contrasted with those of the south of China. Speaking with Irina and Nikolai, it became clear that they thought in terms East and West. Their points of reference were Europe, Moscow, Vladivostok and Japan. China might be just a few minutes away to the south, but for them Heihe was the start of the large and mostly unexplored Asian continent. They might visit Heihe for shopping, and they occasionally dealt with Chinese clients, but there was little other interaction or interest in China.

They talked about their holidays in 'the west' (of Russia) and in South Korea, but seemed indifferent to China and its impact on Blago. It wasn't that they disliked China or feared that China was taking over economically or posing a threat to their region. It was as if China was some other country that just happened to be located nearby. Even the news about the building of a bridge connecting Heihe and Blago did little to stir their enthusiasm for the future of local links between Chinese and Russians.

When I told them about Australians' fears of Chinese buyers snapping up houses in Sydney and Melbourne, they just shrugged. The Chinese weren't interested in in living in Russia, they said, and besides, only Russians could buy property in Russia.

The next day when I visited the Blago museum, I found a similar indifference to what lay across the water. The museum presented the development of Blago as akin to a Russian equivalent of the Wild West or a settlement on the Missisippi. In the old photos of 19th century Blago the town looked like a frontier settlement of miners, hunters and storekeepers served by paddle steamers. The Chinese were portrayed as strange foreign interlopers not unlike the way the Chinese coolies are shown in US accounts of the building of the railroads. The Museum's section on the Defence/Massacre of Blagoveshchesnk was similarly slanted as a heroic local defence against barbaric hordes of fanatic Asiatic. Chinese visitors are allowed to visit the museum but their tour guides have been banned from doing their own explanations to Chinese visitors, after local authorities took exception to their interpretation of events.

Suspicions of China were evident in other areas of Blago civic life. The local authorities were trying shut down the Confucius Institute that had been set up with Chinese government backing at the local university, ostensibly to provide lessons in Chinese language and culture. As in some western countries, the Confucius Institute had come under suspicion as being a "soft power" initiative to establish greater Chinese influence in local affairs. During my visit the institute was being investigated for failing to have the correct paperwork. It looked like China was facing some Russian resistance against it's "One Belt, One Road" strategy of winning influence in neighbouring countries through infrastructure projects and soft power.

Blago sits about 100km south of the Trans Siberian Railway, to which it is connected by a branch line. I had planned to take the train for two days eastward to Vladivostok, and then return to China via the border at the Ussurri river. It was not to be. I had underestimated how difficult it was to communicate and buy tickets in Russia. With just a few days at my disposal, I took the safe option decided to head back over the river to Heihe.

After a wonderful breakfast of blini pancakes and honey provided by my Russian hosts, I said farewell and set off to take the ferry back to China. My hosts were unable to accompany me - they were committed to mundane everyday activities - dropping the kids off at school and having early morning team meetings at the office.

En route back to the Amur riverside I passed through Blago's grim hinterland of power stations and railyards. It was raining and grey Soviet-era concrete apartment blocks lined the potholed road busy with rush-hour traffic. An Antonov jet trailed exhaust smoke from its engines as it flew overhead towards the nearby airport. For a moment I felt like I was trapped in a remote corner of the vast Russian continent.

My last hour in Russia was spent enjoying a final coffee and muffin in an arty waterside cafe. Like the Pushkin Bookshop it was lined with bookshelves, except these contained real book and magazines that were actually read by the customers. A friendly young waitress tried to strike up conversation with me, but our lack of a common language left me struggling with just embarrassed smiles and hand gestures to communicate how good the coffee was. I stopped off at a market to buy a few souvenirs - chocolate, and some kvass fermented drink to take back to Australia. The Asians in the market didn't understand my Chinese - they turned out to be Vietnamese. The Chinese traders had moved back across the river - and in some cases evicted from the apartments - when the economic situation turned sour in 2014.

I was one of just a handful of Caucasians taking the Russian ferry crossing over to Heihe in the early afternoon. I had trouble communicating with the ticket office staff, who didn't seem to want to sell me a ticket. They didn't speak English and it took a few frustrating minutes for me to work that they weren't accustomed to selling one way tickets to China. The Russians always came back. But eventually I was able to get a ticket and through passport control, and on the boat. Within ten minutes I was back in China, where I was once again a foreigner, but I least I could make myself understood.

When I came out of the Immigration building I was besieged by Chinese touts and taxi drivers, yelling at me in Russian. "No thanks," I said to them in Chinese. "I'm not from Russia."